The 9th of May is Rabindranath Tagore’s birthday. Last week, we celebrated the occasion with a melody and a song contribution by Chinmay Mandal –singer and musician from Bali island, Sundarbans who performs across islands in the delta and beyond. His wife Moumita has been a long-time singing partner, as Chinmay stirs up popular melodies on the dotara (stringed musical instrument) and the harmonica. The tune that Chinmay played on his dotara this time as a tribute to the poet is expectedly a Rabindra Sangeet (Tagore songs)– ‘Gram chhara oi ranga matir poth’ (That earth-red village path) and the song he broke into accompanied by the harmonica is ‘Chokher aloy dekhe chilem chokher bahire’ (I had beheld the world with the light of my eye). All these bring us to the point of today’s post: interconnectedness, which is at the heart of Tagore’s compositions.

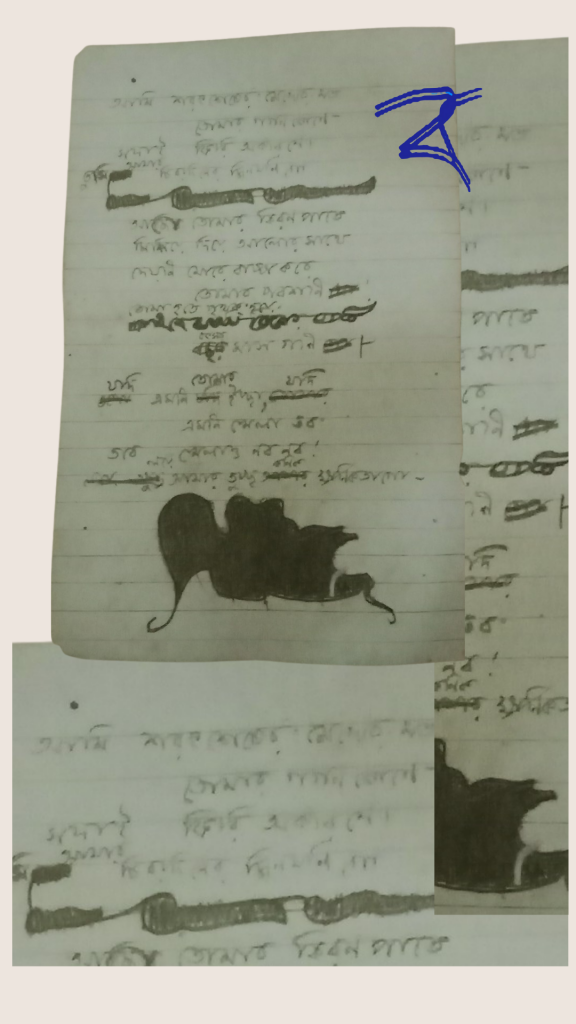

Tagore switched effortlessly between genres and disciplines – poetry and song, writing and doodling, drama and dance, education and play, stories and prose, agriculture and craft. He found a familiar rhythm in all these through his philosophy which reflects a universal ethos. His doodles are famous in how they took shape from what he edited out of his writings.

Delta Lives, too, has been guided by an interdisciplinary fervour because it started in an ecologically fragile ecosystem which is at the forefront of climate disasters, where the abundant creativity has a certain wilderness to it. Local skills have not been organised into sectors, and hence, the creative practices of the community (say stitching or idol-making) have not evolved into clusters. Due to the general lack of specialised education in individual crafts and practices, it’s common for a local inhabitant to take up more than one of the creative forms at different junctures of their (delta) lives. Ramapada Mistry who does carpentry and runs a local homestay business with his wife Hari used to run a local theatre group for visitors and tourists. The theatre group adapted Bono Bibi plays, part of the famous (religious mythological) theatre tradition in the Sundarbans.

These creative forms are more than hobbies for the delta people, nurturing them emotionally and bringing in occasional pay but hardly ever stabilising into professions. There are rare exceptions like Chinmay Mandal who sustains himself and his family through his musical practice. He, however, regrets the lack of a local musical community that can inspire and strengthen his practice. There are performer groups in Dayapur island (Sundarbans) who enjoy a sense of community (more than 35 performer groups live in the region) but unlike Chinmay (and like Ramapada), they have season-specific and overlapping occupations. Most of them do not perform around the year; they also farm and fish and cook for a living.

What ties their varied practices? What brings together different lines of creativity within a family or within the same person? At Delta Lives, we have been exploring that while trying to arrive at a place-based consciousness with the locals and give the various strands of creativity a thematic coherence. We are designing various activities around this, and thinking up visuals to best represent this interconnectedness. One such visual is a social network map, which we proposed to the C3 community when we were pitching for the grant. The map is an artistic manifestation with linkers that are representative of cultural and ecological ethos. It is really the delta and its various elements like the threads and the mangrove roots (of the deltas) which connect the lives of the islanders and run like creeks and channels through their creative pursuits.

We’ll explore more of these Delta Lives activities and visuals which are inciting place-based consciousness and representing interconnectedness in our next two blog posts. Stay tuned.